It’s not illegal to be homeless in the United States - but in many places, it’s illegal to do the things you need to survive while being homeless. Sleeping on a bench. Sitting on the sidewalk. Storing your belongings in a tent. Even asking for food. These aren’t crimes of violence or theft. They’re basic human actions - and in over 1,000 cities across the country, they’re against the law.

Where Sleeping in Public Is a Crime

There’s no federal law that bans homelessness. But cities and counties have passed ordinances that make life on the streets a legal gray zone. In 2024, the U.S. Conference of Mayors reported that 68% of cities with populations over 100,000 have laws that criminalize sleeping in public spaces. Some of the strictest laws are in states like California, Oregon, Florida, and Arizona.

In California, cities like Los Angeles, San Diego, and San Francisco have banned camping on sidewalks, parks, and beaches. In 2023, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that enforcing these bans violates the Eighth Amendment when no shelter space is available - but that ruling was overturned by the Supreme Court in June 2024. Now, cities can enforce anti-camping laws even if shelters are full. Cities like Portland and Seattle still face legal challenges, but enforcement has increased dramatically since the ruling.

Florida has some of the most aggressive anti-homeless laws. In Miami, it’s illegal to sleep on public property between 9 p.m. and 6 a.m. In Orlando, sitting or lying on sidewalks is punishable by a $500 fine. In 2023, the state passed a law allowing police to clear encampments without offering alternative housing - even if the person has no place to go.

Arizona passed Senate Bill 1485 in 2023, making it a misdemeanor to camp on public land within 500 feet of a school, park, or library. Phoenix and Tucson have since cleared dozens of encampments, often without notice. In 2024, the Arizona Supreme Court upheld the law, saying cities have the right to protect public spaces - even if it means pushing people into more dangerous areas.

Oregon saw a surge in anti-homeless ordinances after 2020. Portland’s city council passed a ban on overnight camping in parks and public spaces. In 2023, the state legislature passed a law allowing cities to remove belongings from encampments after just 72 hours of notice - even if the person is still there. The ACLU has filed multiple lawsuits, but most have been dismissed.

Why These Laws Exist - And Why They Don’t Work

City officials often say these laws are about public safety and cleanliness. They point to overflowing trash, blocked sidewalks, and concerns about crime. But data doesn’t support the claim that homelessness increases crime. A 2022 study by the Urban Institute found no correlation between the presence of homeless encampments and rising crime rates in cities like Los Angeles, Seattle, or Denver.

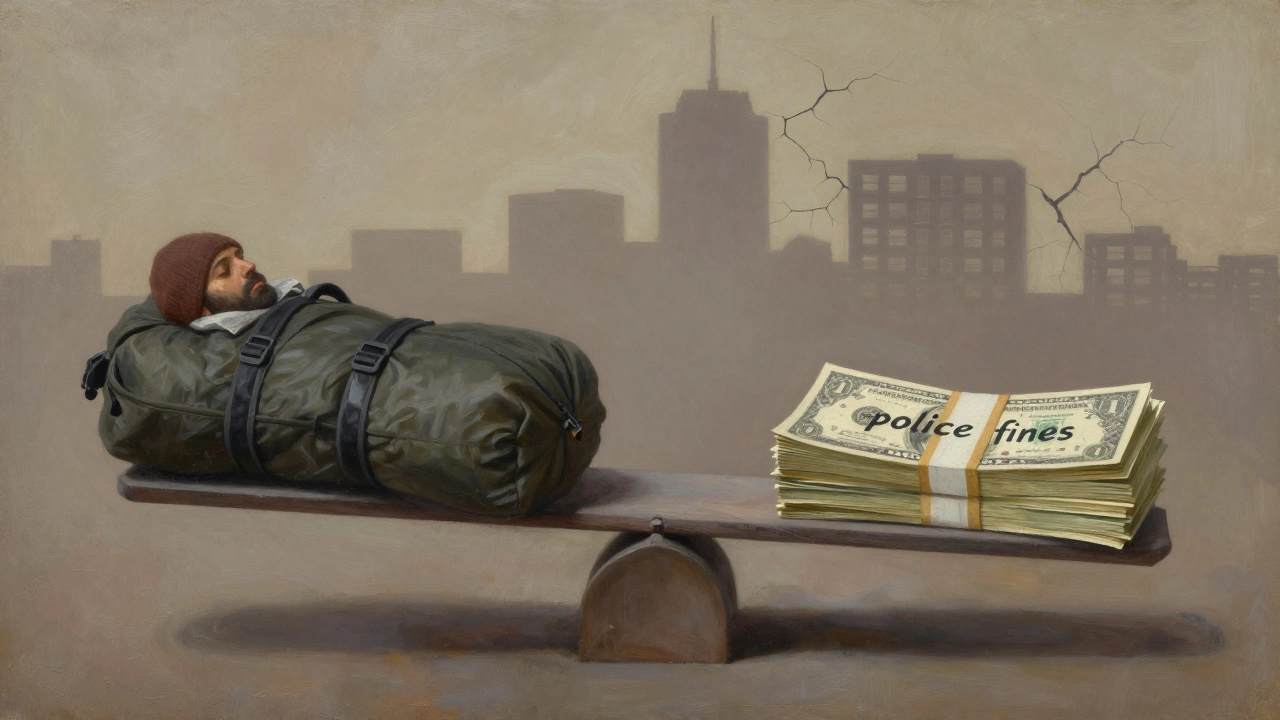

Instead, these laws are a form of displacement. They don’t solve homelessness - they just move it. People who are cited for sleeping on the street often can’t pay the fines. Unpaid fines lead to warrants, which lead to arrests. In 2023, over 12,000 people in California were arrested for sleeping in public - not for theft, not for violence, but for being homeless.

And here’s the cruel irony: these laws make it harder to escape homelessness. A criminal record makes it harder to get a job. Losing your ID during an arrest means you can’t access benefits. Being fined $200 for sleeping on a bench when you have no income means you fall deeper into debt.

States With the Least Harsh Policies

Not all states treat homelessness the same way. Some have taken a different approach - one that focuses on housing, not punishment.

Utah pioneered the Housing First model in 2005. Instead of requiring people to get sober or find a job before getting housing, they gave them homes first - and then added support services. Since then, chronic homelessness in Utah has dropped by 91%. The state doesn’t have laws criminalizing sleeping in public, and most cities provide sanctioned camping areas with access to bathrooms and showers.

Minnesota has a legal framework that protects the rights of unhoused people. In Minneapolis, it’s legal to sleep on the sidewalk - as long as you don’t block pedestrian traffic. The city has also created Safe Sleeping Sites, where people can legally camp with access to water, trash removal, and security. These sites are not shelters - they’re temporary, low-barrier spaces that keep people off the streets without forcing them into systems they can’t access.

Colorado passed the Homeless Bill of Rights in 2020, making it illegal for cities to deny people the right to use public spaces for sleeping or resting. While enforcement is uneven, the law has stopped several cities from clearing encampments without offering alternatives. Denver now has over 30 designated rest zones where people can legally stay overnight.

What’s Really Needed - And What’s Being Ignored

Homelessness isn’t caused by laziness or poor choices. It’s caused by a lack of affordable housing, stagnant wages, mental health crises, and the collapse of social safety nets. In 2025, the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the U.S. is $1,700. The federal minimum wage is $7.25. A full-time worker at minimum wage earns $15,080 a year - $1,257 a month. That’s $443 short of rent alone - before food, medicine, or transportation.

There are more than 650,000 people experiencing homelessness on any given night in the U.S. But there are only about 200,000 shelter beds - and many of those are full, unsafe, or require sobriety, marriage, or a clean criminal record to enter. That means over 450,000 people have nowhere to go - and yet, dozens of cities spend millions enforcing laws that punish them for existing.

Real solutions cost less than enforcement. A 2024 study by the National Alliance to End Homelessness found that providing permanent supportive housing to one chronically homeless person saves taxpayers $15,000 a year in emergency room visits, jail stays, and police responses. That’s cheaper than arresting them.

What You Can Do

If you live in a city with anti-homeless laws, you’re not powerless. Here’s what works:

- Support local organizations that offer legal aid to unhoused people - like the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty or local ACLU chapters.

- Attend city council meetings and demand alternatives to criminalization. Ask for funding for housing, not sweeps.

- Donate to groups that provide hygiene kits, tents, or bus tickets - not just food. People need dignity, not charity.

- Vote for candidates who support housing as a human right - not just for their platform, but for their track record.

Homelessness isn’t a problem you can arrest away. It’s a failure of policy - and it’s one we can fix. But only if we stop pretending that punishing people for being poor will ever make them disappear.

Is it illegal to sleep in your car if you’re homeless?

In many cities, yes. Over 100 cities in the U.S. ban sleeping in vehicles overnight - especially in residential neighborhoods or near schools. Some cities, like Portland and Austin, allow it in designated parking zones. Others, like San Diego and Phoenix, issue fines or tow cars. Even if your car is your home, police can still enforce parking restrictions, loitering laws, or public nuisance ordinances.

Can police take your belongings if you’re homeless?

In most places, yes - and often without warning. Cities like Los Angeles, Seattle, and Phoenix have policies allowing them to confiscate and destroy belongings from encampments after giving 72 hours’ notice. But the Supreme Court has ruled that destroying essential items like ID, medication, or legal documents violates due process. Many lawsuits have been filed over this, and some courts have ordered cities to store belongings for at least 90 days.

Are there any federal protections for homeless people?

No federal law protects the right to sleep in public. But the Eighth Amendment prohibits cruel and unusual punishment - and in 2024, the Supreme Court ruled that enforcing anti-camping laws when no shelter is available may violate that right. That ruling is still being interpreted by lower courts. Some states, like Colorado and Oregon, have passed their own Homeless Bill of Rights, but these aren’t enforceable nationwide.

Do homeless shelters have enough space?

No. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that on any given night, there are only about 200,000 shelter beds for over 650,000 homeless people. Many shelters have strict rules - no pets, no couples, no alcohol, no mental health crises - that exclude most people who need help. In cities like New York and San Francisco, shelters are so full that people wait weeks just to get a bed - if they get one at all.

What’s the difference between criminalizing homelessness and providing housing?

Criminalizing homelessness punishes people for being poor - it costs cities money in policing, court fees, and jail stays. Providing housing - especially permanent supportive housing - saves money and lives. A single person in supportive housing costs about $15,000 less per year than someone cycling through emergency rooms, jails, and shelters. Cities that invest in housing see fewer 911 calls, lower police overtime, and improved public safety. It’s not just ethical - it’s economical.

Next Steps If You’re Affected

If you’re homeless and facing legal trouble, contact your local legal aid office. Many offer free help with citations, fines, or arrests related to homelessness. Groups like the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty can connect you with attorneys who specialize in housing rights.

If you’re not homeless but want to help, don’t just give money. Advocate. Show up at city meetings. Demand housing, not handcuffs. Tell your representatives that homelessness isn’t a crime - and that laws punishing people for survival are both cruel and ineffective.

The truth is simple: no one chooses to be homeless. But we choose - every day - whether to punish them for it, or to end it.